Design of a system for scraping a 3rd party API using serverless

The limmat was chilly 7°C when this was posted. 9 min readAs mentioned in the previous post, I’m collecting hotel booking data regularly, scraping the Booking.com API. I’m making over 1M requests per month to this API and inserting over 100k rows per day to a database. The entire system runs on Google Cloud’s free tier.

This was a great opportunity to learn a new paradigm: serverless computing. “Serverless” is a misnomer as there’s still a server. The main difference to the ’traditional’ paradigm is that instead of renting a server and having it dedicated for your usage, on serverless, a server is only allocated on demand and is automatically ramped down when no longer necessary. I really enjoyed learning something new, it put me in the flow and I was genuinely looking forward to working on this. I specially enjoyed the simplicity of deploying the code to the cloud, with many additional benefits, such as built-in monitoring and logging.

So how does this system work and what are the advantages of serverless?

Goal

I want to collect data to train a model to predict hotel room prices. I’d like to use the following signals in the model:

- City-level occupancy rate

- Hotel-level occupancy rate

- Day of the week of the desired booking date

- Distance in days to the desired booking date

- Price difference to competitors

To be able to get city-level occupancy rates I will need to scrape all hotels in a city. I imagine hotel booking patterns depend on the city (is it a business-oriented city, i.e., most bookings are during the week or is it a touristic city where bookings are mostly done for the weekend), so I will need to scrape a few different ones.

Overview

The system is scraping a touristic city (Ouro Preto, 48 hotels), a business city (Belo Horizonte, 100 hotels) and a mixed city (Rio de Janeiro, 271 hotels). The scraping is done daily and gets pricing for the next 90 days, for a total of ~38k requests per day ((48+100+271 hotels)*(90 days)). Each request gets data for all rooms in a hotel and I collect all of it. The data about every room in every hotel is inserted, resulting in more than 100k rows per day.

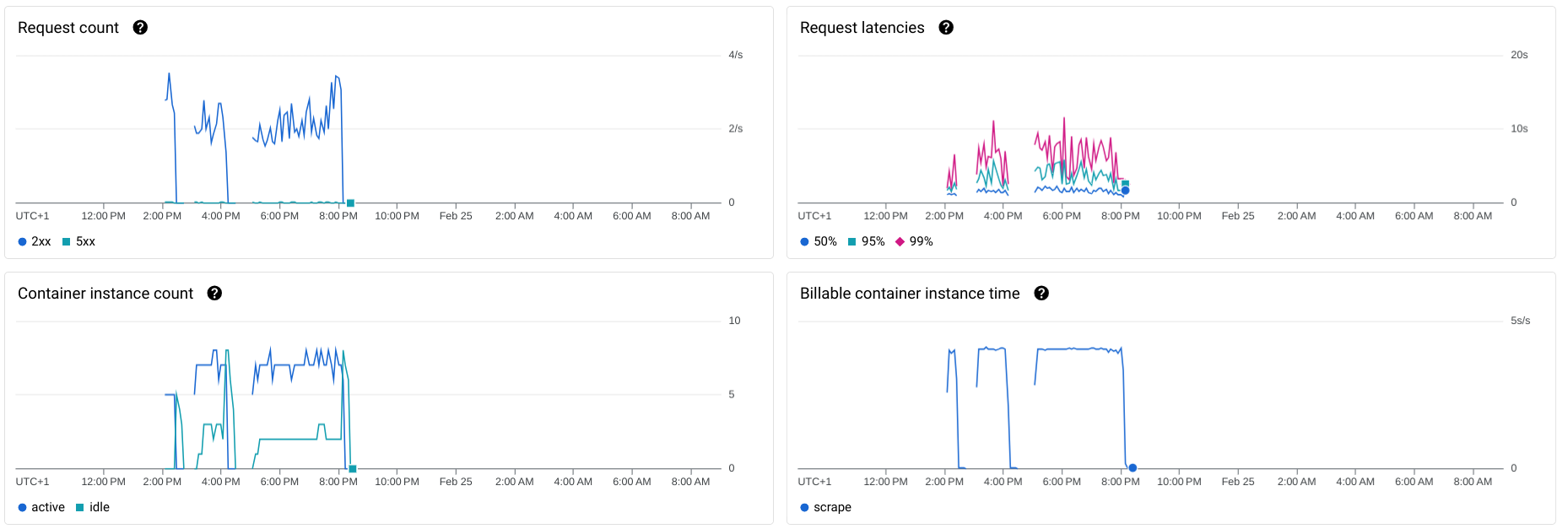

The scraping is kicked off daily by the Cloud Scheduler, which is basically a cronjob on the cloud. It calls a Cloud Function that enqueues all the requests for the next 90 days for a particular city using Cloud Tasks. Each task is a thin wrapper around another Cloud Function that makes a request to the Booking API and writes the results to BigQuery. Both Cloud Functions are implemented using Golang. All of these ‘fancy’ cloud names are part of the serverless paradigm and in the next section we will go over each one of these components to learn what they do.

Component deep-dive

Cloud Scheduler

Cloud Scheduler is the simplest component of the system. As mentioned this is basically a managed scheduler on the cloud, a glorified cronjob. It allows you to execute any task you want at regular intervals. The biggest difference to a regular cronjob is that Cloud Scheduler allows you to trigger another Google Cloud service, such as a Cloud Function. Additionally you can easily monitor its status and configure automatic retries. I appreciate how easy it was to setup.

The free tier allows for 3 jobs.

Cloud Function

Arguably the most important component of the system, Cloud Functions is a very simple way to run code in the Cloud. This is the poster child of serverless, allowing you to maintain and run code without having to set up or manage servers. You pay only for the time your function is executing (rounded to the nearest 100ms) and they get spined up or down according to demand. Cloud Functions is actually powered by Cloud Run, a framework for running applications in a managed environment. Cloud Functions will manage all deployment (including creating a container out of your code) and server infrastructure for you, allowing you to focus on your code. Since I have barely any experience managing servers, I appreciate I can spend time writing code instead of figuring out how containers work, how to keep servers updated, secure, etc.

Typically you want each function to have a single-purpose, e.g. to send an e-mail, process images (e.g. creating a thumbnail of an uploaded image) or run an expensive operation in the background (e.g. create a database). Triggers for functions tend to be events like a user registering an account or an incoming HTTP request. For this system specifically, I have created two functions, one for enqueueing a city for scraping and another for scraping a specific hotel and date.

The free tier allows for 2 million invocations per month, 400k GB-seconds of memory, 200k GHz-seconds of compute time and 5GB of internet data transfer out per month.

Enqueue city

The first function called ’enqueue city’ enqueues a city for scraping for the next 90 days. Specifically, this function is called with different parameters 3 times a day by Cloud Scheduler. It contains a parameter city_id, which indicates which city to scrape:

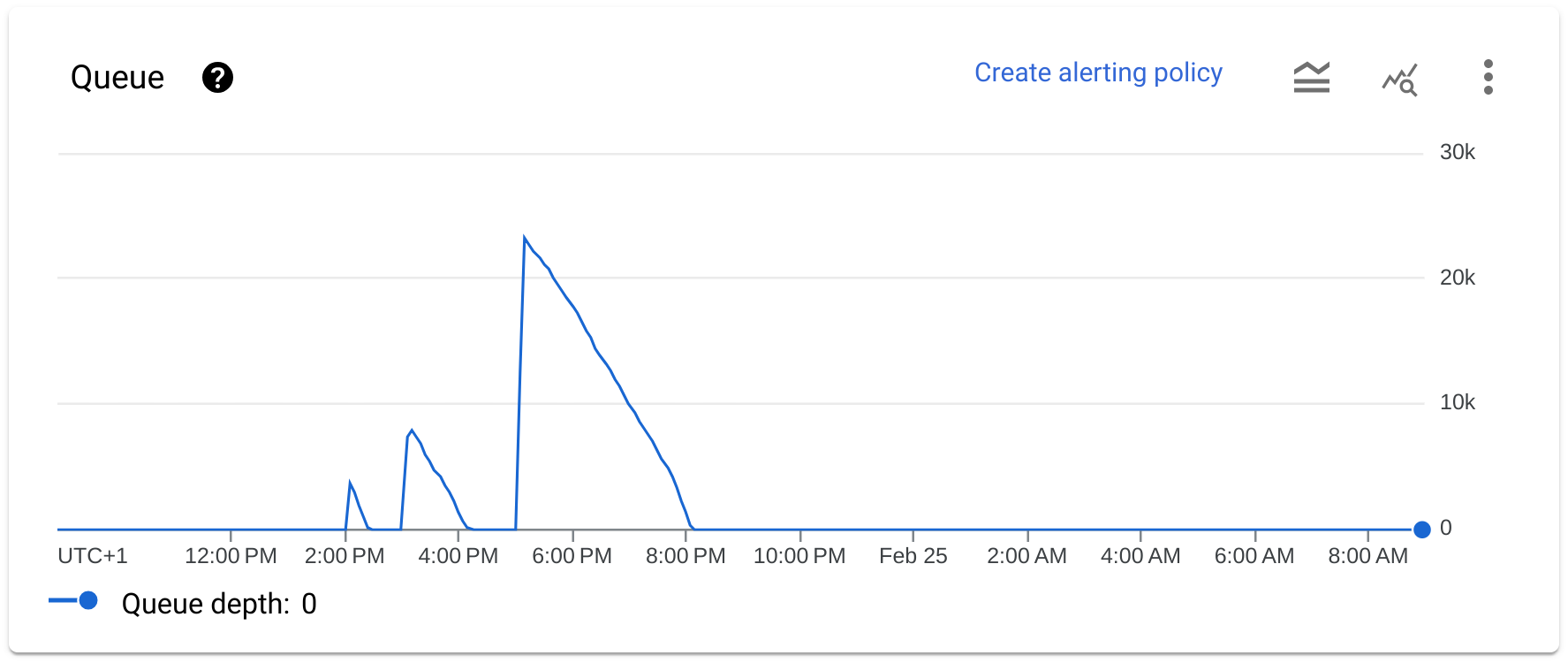

- Ouro Preto is scraped at 2pm, enqueueing 48 hotels*90 days of tasks (4320 tasks).

- Belo Horizonte is scraped at 3pm, enqueueing 100 hotels*90 days of tasks (9000 tasks).

- Rio de Janeiro is scraped at 5pm, enqueueing 271 hotels*90 days of tasks (24390 tasks).

Each task is a parametrized call to another cloud function, ‘scrape’, which makes an external request to the Booking API.

Cloud Function: Scrape Booking.com

This is the core function of the entire system, responsible for making a request to the Booking API to retrieve hotel pricing information. This functions takes checkin_date, checkout_date and hotel_id as parameters.

It does some minimal processing on the output, only keeping the rooms that are double occupancy so that they are comparable across hotels. Typically each room can have different price points, depending on their characteristics: includes breakfast, free cancellation, etc. While this is not necessarily the ideal way to make the data comparable (e.g. a room that has breakfast included should not be compared directly to another one which doesn’t), this is a trade-off that I’m making to make the system simple.

The last step is inserting the processed data into a database, specifically, BigQuery.

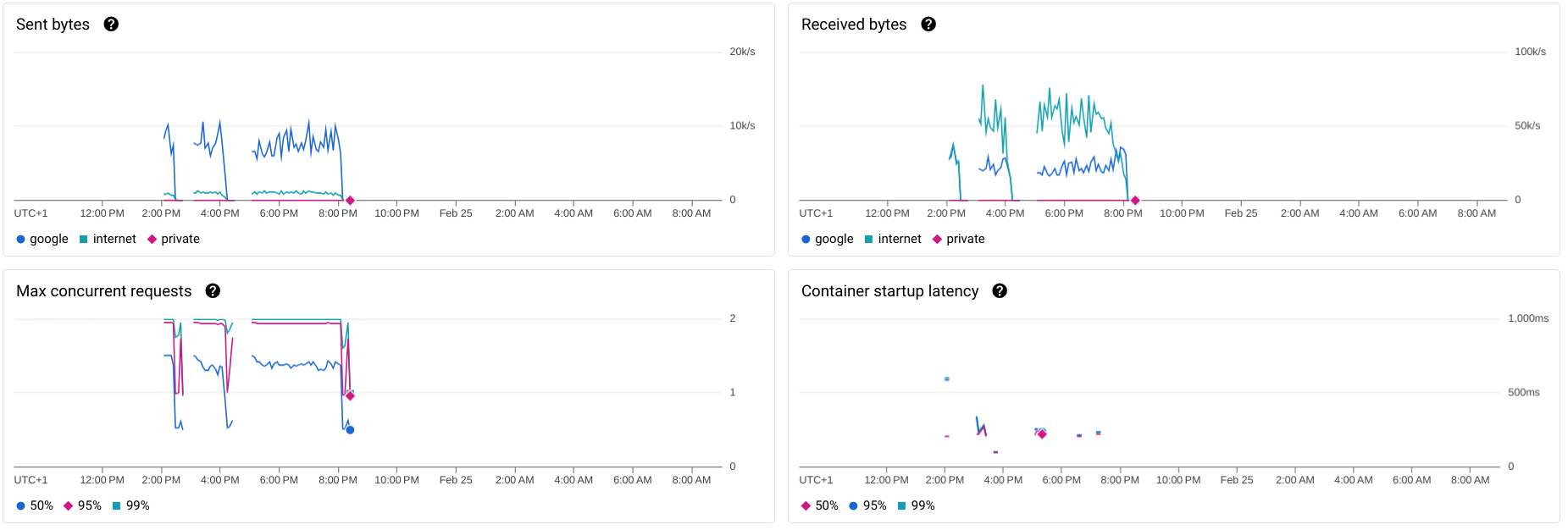

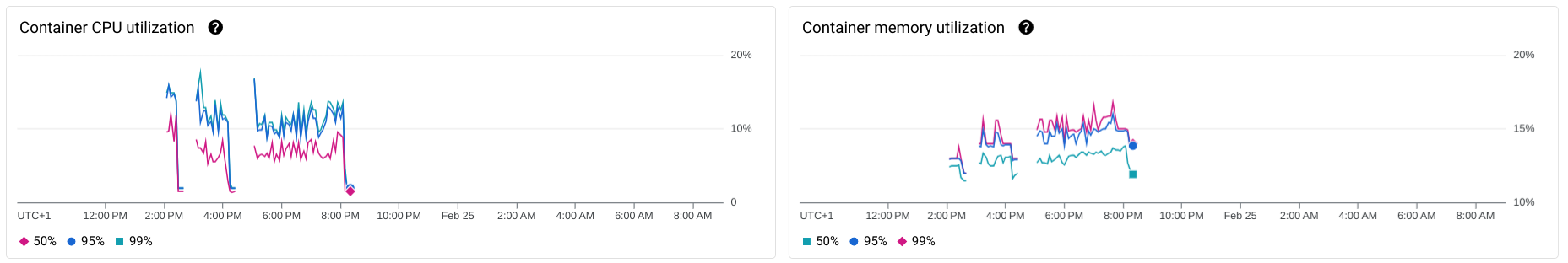

Thanks to built-in monitoring, I can easily see a lot of information about how many resources each Cloud Function is using:

- Sent bytes: ~10kb/s sent to Google itself, ~1kb/s outwards

- Received bytes: ~65kb/s from the internet, ~30kb/s from Google

- Container startup latency: on average takes about 300ms and is always below 1s.

- CPU utilization: Even though I’m only allocating 0.167 CPU (the 2nd-slowest possible setting), I’m still only using on average 10% of that. I guess this is expected, since the function just makes an external request, does some minimal processing and inserts into BigQuery.

- Memory utilization: Averages at 35MB (~15% of the allocated 256MB), which I find surprisingly low given the code has a non-trivial amount of dependencies. I guess this is thanks to Golang being very efficient.

- Through-put: About 3 request per second.

- Request latency: Averages around 6 seconds per request, topping at 10s.

- Container instance count: Tops at 8.

I really like that I get all this monitoring out-of-the-box, with no effort required at all. I can also easily track if any of the functions are returning errors.

Cloud Tasks: Scrape Queue

The external API I’m calling has a rate limit of 8 QPS. Since Cloud Functions don’t support rate limiting, the only way to do this is to use Cloud Tasks, which is basically a task queue in the Cloud. Using a task queue also has other advantages such as ensuring that you will eventually process all enqueued tasks, automatic retries (with backoff settings), controlling the maximum amount of concurrent dispatches, integrated monitoring and direct integration with Cloud Functions.

I’m using Cloud Tasks as a very thin wrapper around a Cloud Function. When a task gets enqueued, its payload carries what function to execute and its parameters. Everyday I can see the peaks of tasks being added to queue (at 2, 3 and 5pm) and the queue gently decreasing in size:

The free tier allows for 1 million operations per month.

BigQuery: Storing room prices

BigQuery is yet another piece of the serverless story, this time for databases. You do not have to worry about how to set it up nor how to scale it and you can analyze data with good old SQL. Specifically I only have a single table that takes checkin_date, room_id, hotel_id, price, rooms_left and scrape_date.

The free tier allows for 1 TiB of query data processed per month and 10 GiB of storage.

First impressions and next steps

Overall, I’m a fan!

I like that I can just focus on coding and don’t have to worry about setting up and managing servers. I’ve used Docker in the past, and since I’m not an experienced sysadmin, it took me a lot of time to get it working. I appreciate that I don’t have to spend time configuring Docker every time I want to add a new dependency. Instead I can deploy the code with a single command line, and Google Cloud will take care of packaging all of it into a container and managing it for me.

Monitoring and logging are a breeze. I can easily search through logs in the Google Cloud UI (across products) instead of having to SSH to a server and become a grep master.

Additionally I’m actually surprised by the somewhat generous free tier. The database now has more than 3.5M rows and I’m still not paying anything for storage or data processing.

One argument against using services is lock-in. For Cloud Functions I would say there’s almost no lock-in, as there’s barely any code related to the cloud functions infra. Everything else is just pure code. Cloud Tasks has a bit more lock-in, as it’s a bit more configuration-heavy. I’m sure if I used Apache Kafka I’d be just as locked-in, though. Arguably the product which is tying me the most to Google Cloud is BigQuery, although I’m not using any of its unique features. It should still be somewhat straight-forward to migrate to a standard relational database such as PostgreSQL.

Next steps

Some of the structure of the system I find quite rigid and I’d like to modify. The function that enqueues city has a hardcoded list of hotels based on the passed-in city_id. I think ideally this function would actually issue a request to the Booking API to get the list of available hotels in a particular date. This will add some complexity to the system but is more future-proof, as it allows for new hotels to be added to the list.

I also want to add more functionality that allows scraping information about the hotel itself, such as its position, name, images of the property and room information.

Finally, I have about one month worth of data and should start some analysis to see how often room prices change overtime and to understand if I’m logging enough information to predict room prices.